By Calvin George

In the process of speaking in multiple conferences in 2024, it was alleged by a leader of the Reina Valera Gomez Society that discrepancies over divine names in the Spanish Reina-Valera 1960 and even 1909 are “the work of the devil.” Notice some of the most egregious excerpts of what was stated:

… he wanted to commit the most blasphemous thing possible, the worst treachery and blasphemy that he could possibly commit against Christ and his name, and sadly he’s achieved it. The devil has managed to erase the mighty and powerful and magnificent precious name of Jesus Christ from the very Book of Jesus Christ, the Word of God. Look, I believe, folks, that this is one of the greatest blasphemies the devil has ever achieved. … Folks, the devil has accomplished a blasphemy that is almost without words can describe it. The 1960, the 1909 doesn’t have it in there, it’s gone. … The precious name of Jesus is gone! It’s gone, 1909-1960, it’s gone. They have been corrupted by the devil. … These deletions of the name of Christ, folks, came straight from hell itself! … we’re being complicit with the greatest scandal and blasphemy of Satan that you can imagine—the removal of the precious name of Jesus Christ from his own Word!

(“The Name above every Name” by Dr. Peter Putney. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3iLnxNLHTYg&list=WL&index=15 Various statements from the 13 to 53-minute mark)

Because some who are uninformed might confuse rhetoric for evidence, the accusations –that discrepancies over divine names in the most common Spanish Bibles are the work of the devil– must be addressed.

Christ does indeed have a name that is above every name. God’s divine names are sacred, and when there is no textual dispute, his name should not removed (and one should obviously not feel obligated to omit a divine name every time there is a textual dispute). I can understand why someone could be concerned about what might seem to be a trend toward minimizing the Lord’s name in various original language editions of the Bible or in its translations. However, divine names have not been exempted from textual variants in the manuscripts as we will demonstrate.

That the devil hates God is already established and need not be proven beyond basic biblical knowledge and human experience. What was not proven, however, is that the difference in divine names in the common Spanish Bible can be traced to demonic acts (what the conference speaker called “the work of the devil” at about the 13-minute mark). There’s a big difference between rhetoric and proof.

The conference speaker chose the worst possible motive –that of a diabolical conspiracy– and did not even bring up the possibility of any other reason and did not provide basic statistics about the number of divine names in the Bibles under consideration. Among possible reasons (and I would add the most reasonable) are the type of mistakes in manuscript copying that are the most common, even among the manuscripts that underlie the Textus Receptus. More on that later.

The conference speaker did not use the term “conspiracy,” but it does not seem too strong a term to describe his theory as to the discrepancies over divine names in the Scriptures, considering his statements, such as “one of the greatest blasphemies the devil has ever achieved.”

The conference speaker presented many personal opinions and theories as if they were incontrovertible and undisputable settled facts. If they truly were settled facts, I would join him and abandon the RV1960. The fact that the devil hates the name of Christ is not sufficient proof that a satanic conspiracy indeed took place in these cases in the Spanish Bible, especially considering there have been variations of the inclusion and exclusion of divine names within Byzantine manuscripts and TR editions, as well as good translations throughout the history of the church.

Let’s consider a number of matters that should help put the issue into perspective:

- Sometimes the KJV does not include divine names that are in the Textus Receptus

- Sometimes the KJV has Bible characters addressing Christ in a routine manner rather than with a divine name

- Sometimes editions of the KJV have had discrepancies regarding divine names

- Sometimes the KJV, RV1960, or the RVG add divine names not in the Textus Receptus

- Sometimes there are divine name differences between editions of the Textus Receptus

- Sometimes differences appear involving divine names in foreign-language Bibles based on the TR as well as English Reformation Bibles that preceded the KJV

- Sometimes the RV1960 does not include divine names that are in the Textus Receptus

- Sometimes there are differences in divine names between the majority of manuscripts and the TR or the KJV

- Sometimes the scribes that copied manuscripts committed innocent mistakes that can be attributed to human nature

- Sometimes scribes changed manuscripts intentionally for well-meaning purposes

- Sometimes scribes changed manuscripts intentionally for evil purposes

- Sometimes Erasmus was confronted with differences over divine names among manuscripts when compiling the Textus Receptus

- Appendix 1 – Table of differences involving divine names in English and Spanish Bibles

Sometimes the KJV does not include divine names that are in the Textus Receptus

Acts 7:20. All TR editions I perused, including Erasmus 1516, Stephanus 1550, Beza 1598, Elzevir 1633, and Scrivener 1881/1894, all have τῷ θεῷ (to God) at Acts 7:20. The KJV leaves this divine name untranslated. The RV1960 and RVG have “Dios” (God). Tyndale 1534, Coverdale 1535, the Great Bible of 1539, Bishops 1568 and Geneva 1587 consistently have “God” in this verse. In all fairness to the KJV, this appears to be a translation issue. Acts 7:20 has “exceeding” in the KJV, and according to Strong’s Concordance, one of the meanings of θεός (God) is that it in can be a Hebraism meaning “very.”

Rev. 16:5. The KJV does not have “the Holy one” as in previous Reformation Bibles (Tyndale 1534, Coverdale 1535, the Great Bible of 1539, Bishops 1568 and Geneva 1587 in different forms, i.e., sometimes lower case) and in TR editions before Beza’s edition of 1582. The RV1960 has “el Santo” (“the Holy one”). In all fairness, the KJV reading “and shalt be” matches Beza’s TR editions from 1582 forwards, and likely subsequent TR editions. Beza has been criticized for basing this change on only one manuscript that he never identified. I’m not affirming that Beza and the KJV are wrong here, just acknowledging some of the complexities behind some divine names that have been added and dropped throughout history for various reasons.

Sometimes the KJV has Bible characters addressing Christ in a routine manner rather than with a divine name

Four examples were noticed while putting together this study:

- The KJV has the woman at the well addressing Christ as “Sir” in John 4:19 when it could have been translated “Lord.”

- The KJV has the nobleman at John 4:49 addressing Christ as “Sir” when it could have been translated “Lord.”

- The KJV has the man who ended up healed at the pool of Bethesda addressing Christ as “Sir” at John 5:7 when it could have been translated “Lord.”

- The KJV has Mary addressing Christ as “Sir” at Jn. 20:15 when it could have been translated “Lord.”

The above four cases are translated as “Señor” (Lord) in the RV1960 and the RVG, and this accounts for some of the differences with divine names between them and the KJV. I don’t consider the above four passages to be wrong in the KJV, as no doubt some in Bible times addressed Christ at times in a respectful manner that did not necessarily involve affirming his deity. The woman at the well and the man healed at the pool of Bethesda apparently did not know who Christ really was at the moment of initially addressing him, and the KJV wording seems to capture this. Jn. 20:15 is very clear that Mary thought she was talking to the gardener when she addressed Christ as “Sir” in the KJV. By this same criterion, it should not be considered wrong for king Nebuchadnezzar to refer to the fourth man in the fire as “semejante a hijo de los dioses” at Dan. 3:25 in the RV1909-1960 when it is not so likely for the pagan king to have instantly recognized the identity of the fourth man in the fire, not to mention the resulting translation does not contradict the underlying words in Aramaic.

Sometimes editions of the KJV have had discrepancies regarding divine names

Considering only the New Testament, the first edition of the KJV in 1611 omitted the following divine names that appear in modern editions:

1 Tim. 1:4 godly (Although “godly” is not considered a divine name, it is included here because, due to language differences, there were seven instances of “godly” in the KJV that were translated as “Dios” (God) in the 1960 and RVG, including this very passage.)

1 Jn. 5:12 God

It is acknowledged that these omissions in 1611 may have been inadvertent due to printing errors.

Sometimes the KJV, RV1960, or the RVG add divine names not in the Textus Receptus

Mark 2:15. “Jesus” only appears once in Mark 2:15 in all the TR editions I have perused. This includes Erasmus 1516, Stephanus 1550, Beza 1598, Elzevir 1633, and Scrivener 1881/1894. “Jesus” appears twice in Mark 2:15 in the 1960, KJV, and RVG, without italics (in all editions I have perused).

Jn. 7:50. “Jesus” does not appear in all the TR editions I have perused. This includes Erasmus 1516, Stephanus 1550, Beza 1598, Elzevir 1633, and Scrivener 1881/1894. The KJV has “Jesus” without italics in Jn. 7:50 (in all editions I have perused). My RVG 2010 (first edition acquired from Chick Publications in 2010 after its appearance was announced) has “El” (He). An RVG I acquired from Chick Publications in 2019 that still stated it was a 2010 edition has “Jesús” at Jn. 7:50. How many other changes of divine names could there be in RVG editions since 2010?

A total of 21 cases of divine names in italics were noticed in the KJV New Testament (when restricted to the divine names listed in the table in the appendix). They are as follows: “God” Luke 2:27; Acts 7:59; 10:36; 26:7; Rom. 9:4; 1 Cor. 16:2; 1 Th. 5:23; 2 Tim. 4:16; Heb. 9:6; 1 Pet. 5:3; 1 Jn. 3:16. “Jesus” Mar. 5:24; 16:9; Luk. 7:37; 19:1; Jn. 9:1. “Christ” Mar. 13:6; Luk 21:8. “Lord” Jas. 2:1. “Holy Ghost” (“Holy,” when first word of “Holy Ghost”) Mat. 12:31. “Son of Man” Mar. 13:34. It is presumed that these divine names are not in the Textus Receptus in their respective passages, but rather added when needed for clarification (which can be a very subjective matter).

A total of 24 cases of divine names in italics were noticed in the RVG New Testament (when restricted to the divine names listed in the table in the appendix). They are as follows: “Dios” (God) Mar. 15:29; Luk. 2:37; Acts 7:59; 10:36; Rom. 3:29; 1 Cor. 16:2; 1 Th. 5:23; 2 Tim. 4:16; Heb. 1:5; 11:6; 1 Pt. 5:3; 1 Jn. 3:16; 5:16. “Jesús” (Jesus) Mar. 5:24; 6:14; 16:9; Lk. 7:37; 11:37; 19:1; Jn. 9:1; Acts 4:11. “Cristo” (Christ) Mar. 13:6; Lk. 21:8. “Señor” (Lord) 1 Cor. 1:2. It is presumed that these divine names are not in the Textus Receptus in their respective passages, but rather added when needed for clarification (which can be a very subjective matter).

At the beginning of many chapters in the Gospels, the RV1960 replaced the pronoun “he” with “Jesus” if there was absolutely no question as to who the pronoun was referring to. This is the main reason “Jesus” appears far more often in the RV1960 compared to the KJV and RVG. In fact, it is very likely that the RV1960 has a total count of more divine names than the KJV and RVG for this very reason. The KJV and the RVG added “Jesus” to the beginning of several chapters as well (see Luke 19:1 and John 9:1), though not as often, but they designated such cases with italicized words. The RV1960 did not use italicized words to designate words added for clarification, as they represent emphasis in modern literature.

Sometimes there are divine name differences between editions of the Textus Receptus

Mark 11:26. The entire verse, which includes a divine name (“your Father”), was not included in at least the first two TR editions by Erasmus. It was included in Stephanus 1546, and it was likely retained in all subsequent TR editions.

Acts 16:7. Beza 1598 has “Jesus.” Stephanus 1550 does not, nor does the 1960, KJV or RVG.

Rom. 12:11. Stephanus 1550 has καιρω (time or season); Beza 1598 has κυρίῳ (Lord). The 1960, KJV, and RVG match Beza 1598.

Phil. 1:14. Colines 1534 has “God.” This divine name is not found in Stephen 1550. The 1960 KJV and RVG versions agree with the latter.

Col. 1:2. Beza 1598, which is the TR edition which the KJV followed the closest, has “Christ Jesus” at the beginning of Col 1:2; the Scrivener Greek text and the KJV retain only “Christ,” following Stephanus 1550.

2 Tim 2:22. Beza 1598 has “Christ” in 2 Tim 2:22 while Scrivener and KJV have “Lord,” possibly following Stephanus 1550.

1 Jn. 2:23 ὁ ὁμολογῶν τὸν υἱὸν καὶ τὸν πατέρα ἔχει is omitted in Stephanus 1550 but included in Beza 1598. This resulted in ten words in italics at the last half of 1 Jn. 2:23 in most printings of the KJV, involving two divine names: (but) he that acknowledgeth the Son hath the Father also. The 1960 and RVG have the entire verse without italics. Tyndale 1534, Coverdale 1535, and Great Bible 1539 omit the phrase, Bishops 1568 places it in brackets, Geneva 1587 places it in brackets in the margin.

1 Jn. 3:16. “God” is not in Stephanus 1550, but it can be found in Scrivener’s Greek text. “God” is in italics in some printings of the KJV of this verse. It is in italics in the RVG.

1 Jn. 5:7. The famous Comma Johanneum. A major part of 1 Jn. 5:7 was not included in the first two Erasmus editions of the TR, which involved three divine names: ὁ πατήρ (the Father), ὁ λόγος (the Word) and καὶ τὸ Ἅγιον Πνεῦμα (the Holy Ghost).

Rev. 14:12. The 1516, 1519, and 1522 edition of Erasmus’ Textus Receptus did not include “God” in Rev. 14:12. “God” was restored in this verse in his 1927 edition, possibly through the influence of the Complutensian Polyglot.

Rev. 16:5. Previously mentioned. Pre-Beza 1582 TR editions had ὅσιος (holy, or “the Holy One” in context), referring to God. Beza changed his 1582 edition to ὅσιος (shalt be). As is the case with some other divine names, “the Holy One” can be seen as either a title or description (adjective), or both.

Rev. 19:6. The 1516, 1519, and 1522 edition of Erasmus’ Textus Receptus did not include “Lord” in Rev. 19:6. “Lord” was restored in this verse in his 1927 edition, possibly through the influence of the Complutensian Polyglot.

Twelve passages with divine name differences among TR editions were just documented, some of them involving multiple divine names in the same passage. There may be more that I am not aware of, as an exhaustive listing of all differences between all TR editions does not exist. I did not include cases of substitution of one divine name for another nor transpositions (such as “Christ Jesus” vs. “Jesus Christ”), which would have made the list longer.

Sometimes the RV1960 does not include divine names that are in the Textus Receptus

There are as many as 18 cases. This approaches the amount of cases of differences of divine names between TR editions I documented earlier, (and the number of TR differences could be higher if we had easily searchable data on all TR editions). All but two of the 18 cases in the RV1960 already have a divine name within the actual verse or a pronoun indicative of a divine name. We are not saying that technicalities don’t matter in the Bible, but there are those who will say that doctrines are affected by discrepancies of divine names in the Reina-Valera when the context does not support their statements, nor do basic and recognized rules of hermeneutics. No doctrine is missing, as no major doctrine hinges on just one or two verses. Sometimes, because of textual differences, one less proof text for a doctrine can result in a translation. For example, Revelation 16:5 (mentioned earlier) cannot be used as a proof text for the holiness of God in the KJV, as is the case with the RV 1909–1960 as well as English Reformation Bibles. However, there are dozens, likely even hundreds of verses in the KJV that teach that God is holy. The variant involves doctrine, but the doctrine does not drop out of the Bible.

That the RV1960 does not matches the TR in a small percentage of cases is true (see https://www.literaturabautista.com/la-base-textual-de-la-reina-valera-1960/ for some analysis and statistics), but that is the historical practice of foreign Bible translations over the centuries. The opinion that foreign-language Bibles should never deviate from the TR in the slightest is a relatively recent view, evidenced by the TR-based translations in major languages (Spanish, German, French, Portuguese, Italian, etc.) that for centuries had a sprinkling of non-TR readings. It has been demonstrated in this study that even the KJV sometimes does not follow the TR, but those cases are admittedly rare. I find it interesting that those advocating for no deviations from the TR in the slightest in foreign translations are not willing to have non-TR readings removed from the KJV, regardless of how few there might be.

Sometimes a reading is vindicated by an English Reformation Bible, such as Bishops 1568 at Lk. 9:43.

Acts 15:11 χριστόῦ (Christ) is also omitted in the manuscripts Erasmus usually followed in the books of Acts (codices GA 1, 2815 & 1816) in forming the Textus Receptus. He may have followed codex 69, which contains χριστόῦ. The case of Rom. 1:16 goes back to 1569 and is vindicated by ancient translations such as the Old Latin, the Syriac Peshitta, Armenian, Coptic, etc. Many other passages follow similar patterns or are addressed individually here: https://en.literaturabautista.com/explanations-problem-passages-spanish-bible-new-testament

Sometimes there are differences in divine names between the majority of manuscripts and the TR or the KJV

Although there are more, below are two examples, one involving an addition and another a subtraction:

Mat. 26:38. The Majority Text and the RV1960 have “Jesus” (Ἰησοῦς), while the TR (Stephanus 1550) has αὐτοῖς (self/unto them, etc.), the KJV has “he,” (no italics) and the RVG has “Él” (he in italics).

Luke 7:31 in the TR, KJV, RVG and RV1960 have “Lord,” which is omitted in the Majority Text.

(The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text 2nd ed. by Hodges and Farstad was used to determine the Majority Text in the above examples).

Sometimes the scribes that copied manuscripts committed innocent mistakes that can be attributed to human nature

Divine names appear well over 10,000 times over the whole Bible. If we arbitrarily went with 10,000 for simplicity and allowed for human error while copying sacred names at half of one percent, this would bring the total to 50. This rate of error should not seem exaggerated considering poor lighting methods during medieval times, no corrective lenses for poor vision, illegible handwriting, Greek and Hebrew letters that look nearly identical, fatigue, copying manuscripts with lacuna (physical defects by natural deterioration, or by insects or rodents), lack of Hebrew vowels, the practice of not separating words with spaces or lack of punctuation during some periods, etc. One also has to account for parablepsis, such as when a copyist skipped material because of homoeoarcton (similar beginning) or (homoeoteleuton (similar ending). This could result in haplography (when a copyist wrote once what should be written twice). Another consideration is that some manuscripts were not copied by visually following an exemplar, but rather by copying while hearing a scribe read from his copy. This was sometimes done in masse in a scriptorium. This led to cases of homophony (confusing words with those of a similar sound) in manuscripts. All this could result not only in omissions and substitutions, but also additions, as in dittography (when a copyist wrote twice what should be written once).

Although God’s Word was preserved as promised, God in his sovereignty chose not to do so in the form of outright miracles that prevented human infirmity, such as when inspiration occurred. In the words of Edward Hills, author of The King James Version Defended, “God’s preservation of the New Testament text was not miraculous but providential.” (Hills, Edward. The King James Version Defended. Des Moines: Christian Research Press, 1984, p. 224)

No doubt many scribes copied the sacred text with care, knowing they were handling the Word of God. Some zealous Jewish scribes refused to write God’s name casually and developed a special ritual. In anticipation of this, they would leave blank spaces for the names, to write them in after they have been to the mikveh (ritual bath). During an extensive period of history, the Tannaim developed strict rules for copying Hebrew scrolls, especially for liturgical use in the synagogues. They would go to the extent of counting letters on a page in their remarkable quest for accuracy. During his collating of manuscripts, Wilbur Pickering discovered 14 Greek manuscripts that were identical within the text of 2 John, 3 John, and Jude. Those are very short epistles, but this is remarkable nonetheless. (Pickering, Wilbur N. God has Preserved his Text! No publisher noted. 2nd ed., 2018, p. 125)

The Byzantine manuscripts are generally known to have been more carefully copied than their Alexandrian “rivals.” Pickering reveals this as follows:

A typical ‘Alexandrian’ MS will have over a dozen variants per page of printed Greek text. A typical ‘Byzantine’ MS will have 3-5 variants per page. (Pickering, Wilbur N. God has Preserved his Text! No publisher noted. 2nd ed., 2018, p. 123)

In spite of valiant efforts, lapsus calami (involuntary and unconscious error or stumble) did occur when copying manuscripts, and this must be recognized when considering such matters as discrepancies surrounding sacred names and when formulating ones thoughts on how preservation occurred.

It’s completely unreasonable to attribute heretical motives without foundation while there are reasonable alternatives at hand.

The following image is an example of apparent innocent human error involving divine names in a manuscript utilized by Erasmus:

The above image is of Acts 10:48 in GA 2816, a manuscript used by Erasmus when compiling his first edition of the Textus Receptus in 1516. Circled in red is an insert between the lines consisting of “Jesus Christ” in Greek in an abbreviated form known as nomina sacra. Apparently “Jesus Christ” was originally left out by mistake, or it may have been added by a corrector after referencing a different manuscript than the one originally copied from. “Lord” already appears in the normal place in this verse, so in the corrected version it ended up with three divine names in this manuscript. The RV1960 has Señor Jesús (Lord Jesus) for this verse. The KJV has “Lord”, and the RVG has Señor (Lord). This is a visual real-life example of how divine names were not exempt from discrepancies in the better manuscripts.

God was at work behind the scenes, although not in the form of outright miracles preventing mistakes in the copying, hence the human element manifested in textual variants including manuscripts underlying the Textus Receptus. In spite of this, we have the Word of God in a form that is trustworthy. We can believe it, proclaim it and trust it.

A few years ago, I conducted a simple experiment with about 40 students in a Bibliology class. I asked each of them to copy a certain verse by hand. They were provided about 3 minutes. Two mistakes were found when the copied verses were compared to printed Bibles. Were two of the forty students that made mistakes being influenced by Satan when they copied their verse? Attributing the worst possible motive to actions when there are more reasonable likely causes is not prudent. In spite of what one might believe about the divine aspect of preservation, it must not be forgotten that there is a human aspect to preservation as well, something that some Textus Receptus editors and its defenders in the past have acknowledged and have written about. It would behoove us to consider what they had to say.

Sometimes scribes changed manuscripts intentionally for well-meaning purposes

As much as we may shudder at the warnings of Rev. 22:18, many who have studied manuscripts are convinced that some of the scribes edited select portions of the text as they copied. This includes orthodox scribes, who would not have done so for malicious purposes. Notice this statement from John Burgon, who spent years collating manuscripts:

I do not say that Heretics were the only offenders here. I am inclined to suspect that the orthodox were as much to blame as the impugners of the Truth. But it was at least with a pious motive that the latter tampered with the Deposit. They did but imitate the example set them by the assailing party. It is indeed the calamitous consequence of extravagances in one direction that they are observed ever to beget excesses in the opposite quarter. Accordingly the piety of the primitive age did not think it wrong to fortify the Truth by the insertion, suppression, or substitution of a few words in any place from which danger was apprehended. In this way, I am persuaded, many an unwarrantable “reading” is to be explained. (Burgon John. The Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels. E. Miller, ed. London: 1896, p. 197)

Sometimes scribes changed manuscripts intentionally for evil purposes

Church history does reveal that there were some, such as Marcion, who attempted to corrupt Scripture. Marcion even edited his own gospel, likely based on the book of Luke, but brazenly expunged much of the content of the first four chapters, and that was just the beginning. Intentional manipulation of Scripture in history is not denied. However, the mere possibility of intentional corruption for evil purposes in a given passage, or the fact that the devil would be delighted if an intentional corruption succeeded in being propagated, does not constitute proof for a given passage in the absence of actual evidence.

Many textual critics acknowledge that most (or perhaps the worst) changes, whether intentional or not, occurred within 200 years of the completion of the New Testament. For further reading on textual corruptions, both intentional and non-intentional, I recommend The Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels by John Burgon.

John Burgon was familiar with discrepancies over divine names in manuscripts and shared some observations worth considering

[Mat. 8:29, an omission of “Jesus” in some manuscripts] So again, in the cry of the demoniacs, Τί ἡμῖν καὶ σοί, Ἰησοῦ, υἱὲ τοῦ θεοῦ; (St. Matt. viii. 29) the name Ἰησοῦ [Jesus] is omitted by Bℵ. The reason is plain the instant an ancient MS. is inspected:—ΚΑΙΣΟΙΙΥΥΙΕΤΟΥΘΥ:—the recurrence of the same letters caused too great a strain to scribes, and the omission of two of them was the result of ordinary human infirmity. (Burgon John. The Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels. E. Miller, ed. London: 1896, p. 66)

Liturgical use has proved a fruitful source of textual perturbation. Nothing less was to have been expected, —as every one must admit who has examined ancient Evangelia with any degree of attention. For a period before the custom arose of writing out the Ecclesiastical Lections in the ‘Evangelistaries,’ and ‘Apostolos,’ it may be regarded as certain that the practice generally prevailed of accommodating an ordinary copy, whether of the Gospels or of the Epistles, to the requirements of the Church. This continued to the last to be a favourite method with the ancients. Not only was it the invariable liturgical practice to introduce an ecclesiastical lection with an ever-varying formula,—by which means the holy Name is often found in MSS. where it has no proper place… (Burgon John. The Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels. E. Miller, ed. London: 1896, p. 69)

Sometimes Erasmus was confronted with differences over divine names among manuscripts when compiling the Textus Receptus

I made a personal study of some textual differences between some portions of Erasmus’ manuscripts involving sacred names. It was very revealing, although it did not shake my confidence in the reliability and trustworthiness of God’s Word. It showed that although God’s Word has been preserved (in words and not just in thoughts), this came about by God’s providence and not by an absolute miracle.

I have no desire to exaggerate the differences between the Byzantine manuscripts on which the Textus Receptus was based. For example, the differences between manuscripts likely affect far less than one percent of the instances of divine names, which can be viewed positively as a sign of God’s protection on the text, considering what has happened with other books of antiquity. However, the differences between Byzantine manuscripts are sometimes more than mere spelling changes or variations in word order as some have suggested. The following are some examples of differences between actual manuscripts that Erasmus used that involve certain divine names. It is not exhaustive and ignores instances of spelling, word order, or differences in suffixes.

Lest one think the discrepancies over divine names are just a matter of Alexandrian manuscripts versus the rest, even Byzantine manuscripts include variants of this nature as we will document. Some unfortunately create simplistic conspiracy theories that come across as if one biblical manuscript says “Jesus,” and another says “Jesus Christ,” the manuscript with “Jesus” (or the choice of that name over the other in a translation) represents a disregard for the name of Christ, or even a diabolical act. We do not always know all the factors behind his decisions, but Erasmus sometimes chose an option with fewer divine names. If Erasmus –who is credited with having laid the groundwork for the vast majority of readings that have remained in the Textus Receptus– did not always opt for the reading with the most divine names, or that consistently reflected the reading of the majority of manuscripts available to him, is an indication that such a choice need not be a nefarious act.

What follows is a list differences I’m aware of involving divine names between manuscripts covering Acts-Revelation that Erasmus had available to him when he compiled the first edition of the Textus Receptus in 1516. I am mostly indebted to the Opera Omnia Desiderii Erasmi Roterodami series for textual data on manuscripts utilized by Erasmus.

Acts 2:30. χριστόν (Christ) along with five other words were omitted from Erasmus’s 1516 edition of the TR. The whole phrase is present in GA 1 and GA 2815, but in GA 2816 three words (not including “Christ” are omitted.

Acts 5:41. Erasmus’ codex GA 2816 has χριστοῦ (Christ) in Acts 5:41 and most manuscripts have Ἰησοῦ (Jesus) according to the Hodges-Farstad and Robinson Pierpont editions; however, no divine name appears in the Received Text editions I have reviewed for Acts 5:41.

Acts 10:48. κυρίου (Lord). Erasmus has “Lord” as only divine name in his first edition of the TR following GA 1, 2815 and 2816 before “Jesus Christ” was added between the lines in the latter (as in the image presented earlier in the present article).

Acts 15:11. χριστόῦ (Christ) is omitted in codices GA 1, 2815 and 2816 used by Erasmus. He may have eventually restored the word upon having access to GA 69, which contains χριστόῦ.

Acts 20:28. This passage is subject to variations in the manuscripts Erasmus utilized. His codices GA 1 and 2815 have both κυρίου and θεοῦ (Lord and God), while 2816 has θεοῦ (God) only. Other manuscripts which he may not have had access to have “Lord” only. Alexandrian and Byzantine manuscripts are mixed in this passage. Most later manuscripts have both “Lord” and “God.”

Rom. 5:21. GA 2817 omits κυρίου (Lord). Erasmus’ codices GA 1, 3, 2815, and 2816 have both κυρίου (Lord) and χριστοῦ (Christ).

Rom. 8:35. GA 2817 has θεοῦ (God). Erasmus’ other codices have χριστοῦ (Christ) instead, as in codices GA 1, 2815, and 2816.

Rom. 14:22. θεοῦ (God) is omitted by GA 2817, which was not the case with Erasmus’ other manuscripts GA 1, 2105, 2815, and 2816.

1 Cor. 1:20. GA 2105 omitted θεὸς (God) as well as eight other words, likely due to homoeoteleuton (same ending). The missing words were subsequently restored in the manuscript by Philip Montanus, a colleague of Erasmus.

1 Cor. 1:27. θεός (God) as well as eleven other words are omitted in GA 2815 and 2817, likely due to homoeoteleuton (same ending) error in the archetype from which they originally copied. This portion is also omitted in Erasmus’ first edition of the TR. This was rectified in his second edition of the TR, matching GA 1, 3, 2105, and 2816.

1 Cor. 2:14. θεοῦ (God) is omitted in GA 2815 (as well as GA 2105 before a correction).

1 Cor. 10:9. The reading of GA 2815 is θεόν (God); the other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2105, 2816, 2817) have χριστόν (Christ), which is what he settled for in his TR.

1 Cor. 16:23. χριστοῦ (Christ) is omitted in GA 2815. The other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2105, 2816, 2817) have χριστοῦ (Christ).

2 Cor. 1:14. GA 2815 has χριστοῦ (Christ). The other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2105, 2816, 2817) do not.

2 Cor. 4:5. GA 2105 has χριστόν (Christ). The other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2815, 2816, 2817) have Ἰησοῦν (Jesus).

2 Cor. 4:14. GA 2105 omits Ἰησοῦ (Jesus). The other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2815, 2816, 2817) have Ἰησοῦ (Jesus).

2 Cor. 6:1. GA 2817 omits θεοῦ (God) which was also omitted in 1516 by Erasmus, although this omission is not supported by his other manuscripts.

2 Cor. 10:7. χριστοῦ (Christ) is omitted in GA 2105. Erasmus includes it following GA 1, 2815, 2816, 2817, but surprisingly in the 1519 annotations he suggested that χριστοῦ (Christ) could have been an explanatory addition.

2 Cor. 11:7. GA 2815 has χριστοῦ (Christ) instead of “God” with little or no other manuscript support.

Gal. 1:6. GA 2817 has θεοῦ (God) which Erasmus adopted for his text in 1516. Five of his other codices have χριστοῦ (Christ), which is what he retained in his second edition.

Gal. 1:12. GA 2817 omits Ἰησοῦ (Jesus).

Gal. 3:27. GA 2817 omits χριστὸν (Christ).

Eph. 1:3. χριστῷ (Christ) is the reading of GA 1, 2105, 2815, 2816, 2817; GA 2105 and 2816 (via corrections) add Ἰησοῦ (Jesus).

Eph. 4:30. θεοῦ (God) is omitted in GA 2815.

Eph. 5:21. GA 2816 has χριστοῦ (Christ). The other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2105, 2815, 2817) have θεοῦ (God).

Eph. 5:29. GA 2105 has χριστός (Christ), whereas the other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2815, 2816, 2817) have κύριος (Lord).

Php. 1:26. By an apparent scribal error, GA 2817 adds a further χριστοῦ (Christ) after χριστῷ Ἰησοῦ (Christ Jesus).

Col. 1:2. κυρίου Ἰησοῦ χριστοῦ (Lord Jesus Christ) is omitted by GA 2105 and 2816. It was included in GA 1, 2815, 2816 (with the correction) and 2817.

Col. 3:22. GA 2105 has κύριον (Lord), whereas the other manuscripts available to Erasmus that contain the passage (GA 1, 2815, 2816, 2817) have θεόν (God).

Col. 4:12. GA 1, 2105, 2815 and 2817 have χριστοῦ (Christ); whereas GA 2105 omits it before a correction.

1 Thes. 1:1. GA 2105 omits a clause with eight words that include four divine names: ἀπὸ θεοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν καὶ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ χριστοῦ. Erasmus follows GA 1, 2815, 2816, and 2817 without the omission.

1 Thes. 2:8-9. GA 2815 changes θεοῦ (God) to χριστοῦ (Christ).

1 Thes. 4:2. GA 2105 and 2817 add χριστοῦ (Christ).

2 Thes. 1:8. GA 2105 and 2815 omit χριστοῦ (Christ). GA 1, 2816, and 2817 do not.

2 Thes. 1:12. χριστοῦ (Christ) is omitted by GA 1 and 2815.

2 Thes. 2:2. GA 2105 and 2815 have κυρίου (Lord); GA 1, 2816, and 2817 have χριστοῦ (Christ).

2 Thes. 2:8. GA 2105 adds Ἰησοῦς (Jesus).

2 Thes. 2:13. GA 2815 omits θεῷ God).

1 Tim. 1:1. GA 1, 2815, 2816 and 2817 have Κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (Lord Jesus Christ); GA 2105 has Κυρίου Ἰησοῦ (Lord Jesus) omitting Χριστοῦ (Christ).

1 Tim. 1:2.

GA 1 Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ (Christ Jesus)

2105 Κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (Lord Jesus Christ – the reading Erasmus chose)

2815 Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ (Christ Jesus)

2816 Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ (Christ Jesus)

2817 Κυρίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (Lord Jesus Christ, original uncorrected); Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (Jesus Christ, corrected reading).

Philemon 1:8. χριστῷ (Christ) is omitted in 2816 and 2105 (via a corrector), both manuscripts utilized by Erasmus.

Heb. 13:20. Codex 2816 has Χριστόν (Christ). Codex 2105 omits Κύριον and Ἰησοῦν (Lord Jesus).

James 5:11. Erasmus codices GA 1 and 2816 omit one case of Κύριος (Lord).

Rev. 1:8. κς ο θς (nomina sacra abbreviation for “the Lord God”) is in GA 2814, the sole manuscript that Erasmus had for the book of Revelation when he compiled the first edition of the TR in 1516. Erasmus settled on κυριος (Lord), and did not include “God” in the Textus Receptus for this verse.

Rev. 9:4. θεοῦ (God) is omitted in the 1516-1522 editions of the TR. This is likely due to the omission in GA 2814. Erasmus may have restored “God” from the Complutensian Polyglot.

Rev. 12:17. GA 2814 has Ἰησοῦ (Jesus), but does not have Χριστοῦ (Christ).

Rev. 14:5. Θεοῦ (God) as well as four other words are missing from GA 2814.

Rev. 14:12. θεοῦ (God) is omitted in Erasmus’ first edition of the TR in 1516 due to GA 2814. He may have restored “God” from the Complutensian Polyglot.

Rev. 16:1. θεοῦ (God) is omitted in GA 2814. Erasmus may have restored “God” from the Complutensian Polyglot if it wasn’t in his first edition of the TR.

Rev. 16:5. κύριε (Lord) is omitted in GA 2814.

Rev. 17:6. Ἰησοῦ (Jesus) is omitted in GA 2814.

Rev. 19:6. κύριος (Lord) is omitted in GA 2814. Erasmus may have restored “Lord” from the Complutensian Polyglot if it wasn’t in his first edition of the TR.

Rev. 21:3. θεὸς (God) is omitted in GA 2814.

Most of the time Erasmus goes with what the majority of his manuscripts have for divine names, or the reading with most divine names, although there were exceptions.

The purpose of bringing out this documentation is not to leave people unsettled; however, it is not accurate to go the other extreme and pretend like there has been consistency throughout translations in church history or in what are considered to be the better manuscripts. The situation is indeed complicated, regardless of how much the conference speaker tried to deny it.

Revealing surprising details about non-Alexandrian manuscripts might clash with some views of “perfect” preservation or “pure” manuscripts, but if a view depends on ignoring the actual manuscript record, such a view needs to be re-examined for technical accuracy. God’s Word has indeed been wonderfully preserved, but any preservation view must not only agree with His Word, it must not contradict manuscript history.

Absolute certainty is unquestionable in the original manuscripts. However, some seem to insist that nothing less than absolute certainty in every non-doctrinal technicality is acceptable in preservation. On one hand, such a desire is admirable, but we must be realistic and transparent with what has indeed been preserved for us, which provides adequate, wonderful, trustworthy certainty, even though it may not meet the threshold of absolute certainty in every non-doctrinal technicality as in the original autographs.

Erasmus in his own words on discrepancies over divine names in Scripture:

What shall we do about the Greeks, who read the appointed scriptures out of the Gospel text and for this reason sometimes add the name “Jesus,” taking it from the preceding passage, or put the name instead of the pronoun “his”? What shall we do about our liturgical practice, when we routinely add “In those days Jesus said to his disciples,” when the Gospel does not always have the phrase there? What shall we do about Saint Luke, who left out a part of the Lord’s prayer? Or about the Latin translator, who left out the conclusion found in the Greek – an omission of which Lee does not approve? But to avoid the impression that I am joking in a serious matter, let me say that there were variants in the Greek manuscripts in Origen’s time, there were variants in Ambrose’s and Augustine’s time. Today too there are variants in a number of passages, and yet the authority of sacred Scripture does not waver. (Collected Works of Erasmus. Vol. 72, Ed. Jane Phillips. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005, pp. 77-78)

[Regarding Mat. 1:18, where Erasmus’ TR has Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ] “But I suspect that ‘Jesus’ was added either by a scribe or out of the practice of ecclesiastical recitation.” (Krans, Jan. Beyond What is Written. Boston: Brill, 2006, p. 35)

The following is not a direct quote from Erasmus, but rather a summary of what Erasmus wrote by a historian:

At Rom 1 note 54 Erasmus’ argument is based on stylistic considerations. The Greek manuscripts vary, The Greek manuscripts vary, some reading ‘God,’ others the pronoun ‘his.’ Erasmus translates the pronoun, noting that’ “God” occurred shortly before – it would be somewhat harsh to repeat it immediately afterwards.’ (Rummel, Erika. Erasmus’ Annotations on the New Testament. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986, p. 116)

Was Erasmus doing Satan’s bidding when he decided not to adopt a reading that had a divine name in one of the manuscripts on his table, or when incorporating a divine name that wasn’t in the majority of manuscripts available to him when he compiled the TR? Of course not, and that is not being alleged, but if the logic used in the conference speech we are responding to was taken to its logical extent and applied to Erasmus, this would be the natural conclusion of such a simplistic approach.

I do not mean by what I have presented that some words of Scripture have been lost and never recovered (Mark 13:31). John Burgon explained it this way:

But I would especially remind my readers of Bentley’s golden precept, that ‘The real text of the sacred writers does not now, since the originals have been so long lost, lie in any MS, or edition, but is dispersed in them all.’ This truth, which was evident to the powerful intellect of that great scholar, lies at the root of all sound Textual Criticism. (Burgon, John. The Traditional Text. 1896, p. 26)

The above observation, although not as specific as some would like, provides an answer that remains consistent. By teaching that only the original manuscripts are inspired and infallible, one’s view can remain consistent for all time periods and all languages. I use the KJV in English, and consider it reliable, trustworthy, and proven. By holding to this (that only the original manuscripts are inspired and infallible), I don’t struggle to give a clear answer when asked where the inerrant Word of God was before 1611, for example.

It was alleged in the conference speech that the matter before us is “pretty easy” and “not a complicated issue”

The context of the following quote from the conference speech starts with the story of a missionary who used the RV1960 affirming that there are some complicated issues involved. Then the conference speaker responds with strong disagreement:

“Brother,” he said “this is a complicated issue; it’s complicated, brother.”

I’m sorry, but it’s not that complicated to me. This Bible erases the name of Christ in over a dozen places! This one doesn’t! Which one should we use? It seems pretty interesting, pretty easy to me, despite what some missionaries will tell you, this is not that complex of an issue. A child can understand this. … It’s not a complicated issue.

Dismissing details by belittling someone who pointed out there were some complexities in the matter and going the easy route of attributing diabolical motives without proof is not the right approach. If the 1960 is used by the overwhelming majority of Fundamental Baptists as the conference speaker affirmed, it deserves better treatment. Is considering details (who most would consider to be complex) and putting the facts on the table too much to ask for?

Westcott and Hort are thrust into the matter

The conference speaker brought up Westcott and Hort, who compiled an influential critical Greek NT in 1881 based overwhelmingly on the Alexandrian text. He brought up some unbiblical activities on their part, including participation in a séance. Although I believe it is fair and proper to evaluate unbiblical practices, this should not be a substitute for analyzing their views (otherwise it becomes a purely ad hominem argument). I have written considerably against their textual views here: https://www.literaturabautista.com/critica-de-la-critica-textual/

Nearly all the passages the conference speaker complained about concerning divine names had precedent in the Spanish Bible in the 1862 edition or before (at least five going back to 1569), which pre-dates Westcott and Hort’s 1881 text. Of 18 disputes over divine names in the RV1960, 15 were omitted in the Reina-Valera lineage in the 1862 edition or earlier. This results in 83% of cases before Westcott and Hort’s 1881 text. If one case of Jesucristo (two divine names incorporated into one word) enclosed in brackets in older Spanish Bibles is included, 17 of 18 cases were before 1881 (94%). If the conference speaker was trying to imply that the discrepancies over divine names in the Spanish Bible can be linked to two controversial figures, the historical timeline does not add up!

Conclusion

The only documentation offered by the speaker (related to manuscripts where the alleged motive was to eliminate divine names for reasons of hatred) since the conference was based on a general historical statement or two about some manuscripts being changed for nefarious purposes, but those manuscripts are not identified, nor which specific passages were affected, nor does the document state that the motive was precisely hatred for divine names.

One reason I bring up the issue of “specific passages” is because, as documented, there are passages in the various Byzantine manuscripts, TR editions, KJV editions, and pre-1611 English Bibles that demonstrate differences in divine names. If such did not involve diabolical motives, he would have to prove that it was indeed the case with passages in the RV1960, but somehow not so in the other passages of Byzantine manuscripts, TR editions, KJV editions, and pre-1611 English Bibles.

Should we disrupt all Spanish ministries that use the RV1960 and call all missionaries home using the RV1960 or issue them ultimatums to quit using it based on an unproven hypothesis? The speaker did not call for this outright, but would it not be the effect if his rhetoric was taken literally? The conference speaker has not proven what he alleges. If he could prove that these cases of missing divine names are indeed satanic and not stemming from other problems that afflict even the better manuscripts (slips of the pen, dropping a line, transpositions, incorrect memory, etc.), I would be the first to be on board to restore these precious names to all foreign Bibles, no matter how respected they might be, or how God is using them, or regardless of how close they may already be to the Textus Receptus. In his insistence that the discrepancies over divine names “came straight from hell itself,” it seems he is mistaking his rhetoric for facts, his assertions for proof, his reiteration of either as an accession of evidence.

I’ve said many times that the problem with the RVG is not so much the text, but the movement behind it. The latest divisive rhetoric by its leaders represented by the RVG Bible Society is nothing short of tragic and representative of the baggage associated with the RVG. Even if someone were to be convinced for whatever reason that the 1960 is not the Spanish Bible for them, there are other TR-based alternatives to the RVG. There is no need to legitimize their divisiveness by adopting their text.

I leave you with one last quote from John Burgon:

Our business as Critics is not to invent theories to account for the errors of Copyists; but rather to ascertain where they have erred, where not. … it is by no means safe to follow up the detection of a depravation of the text with a theory to account for its existence. Let me be allowed to say that such theories are seldom satisfactory. Guesses only they are at best. (The Last Twelve Verses of Mark, pp. 100-101)

God has not failed us, we have His Word, and we should read it, love it, believe it, proclaim it, distribute it, and preach it for His glory!

We welcome corrections to this article from our readers.

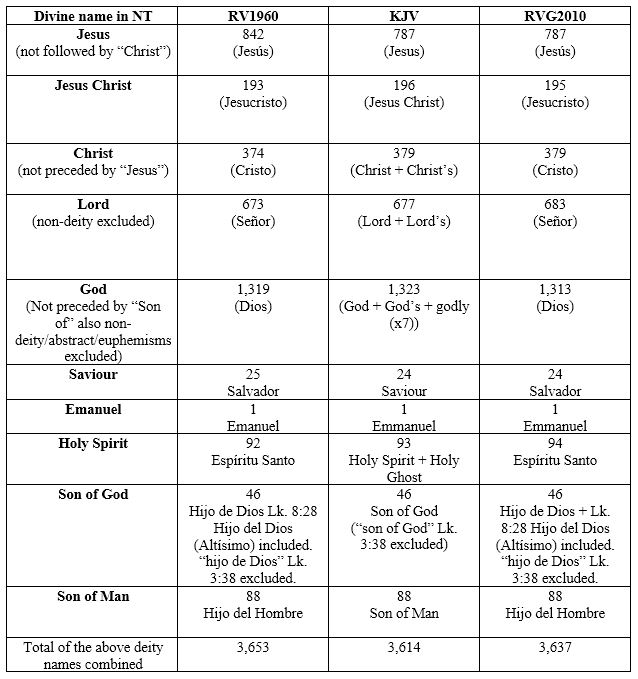

Appendix 1 – Table of differences involving divine names in English and Spanish Bibles

The following table reveals the number of times each respective divine name appears in each translation of the New Testament. Merely counting how many times a sacred name was used in each translation would not have revealed a fair picture in a number of cases because of overlap involving language differences. For example, seven cases of “godly” in the KJV were translated with “Dios” (God) in the RV1960 and RVG. Although it complicated matters, I made an effort to prevent overlap in order to avoid double-counting or under-counting. The table reveals the totals after factoring in such matters as cases of Señor/Lord not referring to deity, (as is the case in many parables) and “Jesus Christ” appearing as one word in Spanish (Jesucristo). All the fine print and sources for statistics are provided at the end.

We welcome corrections to the above table to ensure accuracy. The fine print at the very end should be reviewed first.

The above chart is not exhaustive. Other divine names could be added to the above table. For example, “Son” (in reference to God the Son), “Father” (in reference to God the Father), “Spirit,” etc., but it would also involve the laborious task of separating and documenting deity from non-deity, as had to be done with “Lord.”

There are a number of times when deity is implied in the Greek or Hebrew text, but not stated outright. This leads to some disparity among translations.

All cases of “Holy Spirit” in the KJV appearing as “holy Spirit” (lower case in first word) were counted. Seven cases of “godly” in KJV were counted because they were translated as “Dios” (God) in the RV1960 and RVG. All cases in which divine names appeared in italics in the KJV and RVG were included in the statistics in the table. If they had been excluded, the figures for the RV1960 would have improved for some of the divine names.

Sources and fine print for statistics in the table

For the KJV and RV1960, the text was drawn from blueletterbible.org. For the RVG, in order to ensure the most recent text was used, it was drawn from https://reinavaleragomez.com/source-code.html (updated on September 30, 2024 according to notice on webpage).

Some divine names were straightforward with no anomalies between languages. Others require further explanation, which is provided below.

Jesus

“Jesus Christ” appears as one word in modern Spanish, therefore an effort was made to distinguish when “Jesus” appears apart from “Jesus Christ.”

983 times in 942 verses. “Jesus Christ” appears 196 times in 187 verses in the KJV. 983-196=787

Christ

“Jesus Christ” appears as one word in modern Spanish, therefore an effort was made to distinguish when “Christ” appears apart from “Jesus Christ.”

559 times in 522 verses. “Christ’s” 16 times in 14 verses. Subtotal: 575. “Jesus Christ” 196 times in 187 verses in the KJV. 575-196=379

Son of God

Luke 3:38 is non-deity. Luke 8:28 was included because it is expressing the exact same thing in the RV1960 and RVG, but because of the contraction, one word has an extra letter, meaning it could come up missing when searching digitally by exact phrase.

God

God as a euphemism when not in the Greek (“God forbid”) was excluded. 15 cases in the KJV, 1 in RV1960, 1 in RVG as follows:

Luk. 20:16 God forbid (KJV) ¡Dios nos libre! (1960) ¡Dios nos libre! (RVG)

Rom. 3:4 God forbid (KJV) De ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 3:6 God forbid (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 3:31 God forbid (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 6:2 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 6:15 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 7:7 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 7:13 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 9:14 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 11:1 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Rom. 11:11 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

1 Co. 6:15 God forbid. (KJV) De ningún modo (1960) ¡Dios me libre! (RVG)

Gal. 2:17 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Gal. 3:21 God forbid. (KJV) En ninguna manera (1960) ¡En ninguna manera! (RVG)

Gal. 6:14 God forbid. (KJV) lejos esté (1960) lejos esté (RVG)

There were a few cases in which the term “God” appears in an abstract form, also resulting in differences in capitalization. Take Phlp. 3:19 as an example: “cuyo dios es su vientre” (RVG) and “cuyo dios es el vientre” (1960); compare with “whose God is their belly” (KJV). The following five passages were excluded from the count due to the abstract form regardless of capitalization:

Acts 7:43; 12:22; 28:6; 2 Cor. 4:4; Phlp. 3:19.

For RV1960

1,371 times in 1,193 verses, minus one case as a euphemism (Lk. 20:16), 5 cases non-deity/abstract, minus 46 “Hijo de Dios” = 1,319

For KJV

1,366 times in 1,190 verses. “God’s” 16 times in 15 verses. Subtotal: 1,382 “Godly” 7 times where it is translated as “Dios” in 1960 and RVG. Subtotal: 1,389. Minus 15 cases as a euphemism. Subtotal 1,374. Minus 5 cases in the abstract form. Subtotal 1,369. Minus 46 “Son of God” = 1,323

For RVG

1,365 minus one case as a euphemism (Lk. 20:16). Subtotal 1,364. Minus 46 “Hijo de Dios” = 1,318. Minus 5 cases non-deity/abstract =1,313

Lord

This divine name was the most complex. The following cases of the term “Lord/lord” were deemed non-deity:

Mat. 10:24; 10:25; 18:25; 18:26; 18:27; 18:31; 18:32; 18:34; 20:8; 21:30 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has sir]; 21:40; 24:45; 24:46; 24:48; 24:50; 25:11; 25:18; 25:19; 25:20; 25:21 [twice]; 25:22; 25:23 [twice]; 25:24; 25:26; 27:63 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has Sir]; Mar. 12:9; 13:35 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has master]; 14:14 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has goodman]; Lk. 12:36; 12:37; 12:42 [second mention]; 12:43; 12:45; 12:46; 12:47; 13:8; 13:25 [twice]; 14:21; 14:22; 14:23; 16:3 [KJV & RVG only, 1960 has amo]; 16:5 [KJV & RVG only, lord twice, 1960 has amo twice]; 16:8 [KJV & RVG only, 1960 has amo]; 19:16; 19:18; 19:20; 19:25; 20:13; 20:15; Jn. 12:21; [1960 & RVG only, KJV has Sir] 13:16; 15:15; 15:20; Acts 25:26; Rom. 14:4 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has master]; Gal. 4:1; 1 Pt. 3:6; Rev. 7:14 [1960 & RVG only, KJV has Sir]

There were a few other verses of which there might be a dispute as to whether a reference to “Lord” should be consider deity or not. However, in those very places, the 1960, KJV and RVG matched in their word for “Lord” in the respective verse and language, and so it was a “wash.”

For RV1960

731 times in 674 verses. 731 minus 58 cases non-deity = 673

For KJV

“Lord” occurs 715 times in 657 verses. “Lord’s” occurs 17 times in 17 verses. Subtotal: 732. 732 minus 55 non-deity = 677

For RVG

745 minus 62 cases non-deity = 683

Leave a Reply